We were so exhausted after climbing Monte Perdido that we bailed out from trekking to Refugio Pineta as we had originally planned. The weather was still sunny and clear, the perfect conditions to climb high peaks, so we decided to take a day off before climbing Pico Aneto, the highest mountain in the Pyrenees at 3,408 metres.

We had plenty of climbing and trekking books of Spain but there was nothing in them about Pico Aneto. The only sources of information we had available was via searching on the web and contacting the Refugio.

The starting point of the trek is La Besurta, a car park 10 kilometres from Benasque, the village at the head of the valley. We arrived at the village late in the evening. The plan was to rest most of the next day, drive to La Besurta car park in the afternoon and walk up to the refuge to spend the night.

We spent most of the resting day finding out about the route. The climb is not technically difficult, however it is not designed for the casual walker.

Aneto’s terrain is mainly made out of big and bulky rocks which needed to be scrambled and walked on with care and good balance. This is a very tiring way to climbing a mountain. Therefore, some experts advise to climb this peak during winter, when the snow covers the boulders. However, winter brings its own additional hazards.

We felt capable enough to climb the boulders. What worried us most about the route was the following three risky points; the Portillon Superior, the glacier and the Paso de Mahoma.

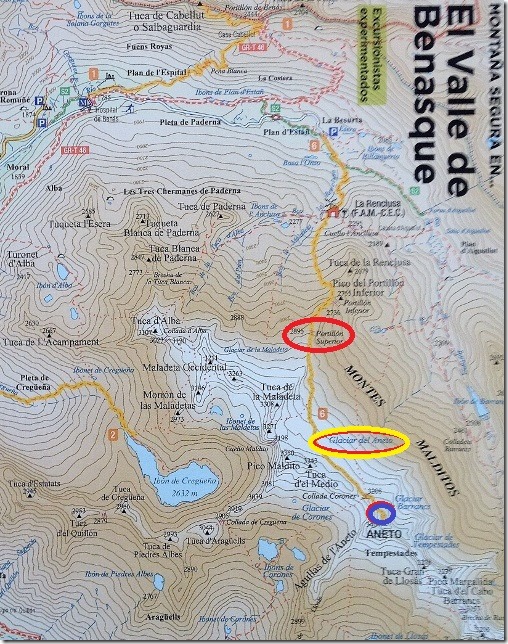

The Portillon Superior (in red on the map below)

The refuge sits in a different valley from Pico Aneto and it is separated from the summit by a long, high, rocky ridge, which you need to cross. There is only one sensible place in which you can breach the ridge, known as the Portillon Superior. This is further complicated because there appeared to be several other viable passing points that can confuse the unwary mountaineer.

Other climbers had not been able to find the pass that easily as it is very narrow and hidden between two high rocked towers. After wasting several hours trying to find the route through the ridge they had to retrace their steps. And believe me, you cannot afford to waste time on Pico Aneto, especially now the days are shorter.

The glacier (in yellow on the map below)

Glaciers can be lethal if they are covered in snow because it prevents you from seeing crevasses.

The glacier worried me. Gary has a bit of experience but I have none. There are techniques you need to know in case you or your partner falls into a crevasse. We tried to learn them by watching an alpine climbing DVD we had taken with us. However, everything made sense on TV but, would I be able to remember all of these techniques in a rescue situation up there.

El Puente de Mahoma (blue on the map below)

The final chapter of the route. It is short, no more than 30 metres in length. It is not difficult. An exposed ridge of rocks that tests your vertigo.

The night before we called the refuge to find out more about the route and the weather conditions. The host sounded impolite and unfriendly on the phone. He answered all my questions monosyllabically with either a “yes” or “no”. This exacerbated my anxiety and I was getting incredibly frustrated. I needed to know all the potential threats on this mountain in detail.

I also wasn’t impressed about this guy’s customer service, however, he did give us one crucial piece of information. “Forget about compasses”, he said. “If you want to succeed on this mountain you must carry an altimeter and a good map”. The altimeter was primarily to locate the Portillon Superior. “You have to reach an altitude of 2,895 metres. At this point, you have to be able to see a relatively easy path to the other side of the ridge. If any of these two elements are missing, you are not in the right place” he said. Following his advice, we downloaded a free altimeter called ‘Altimeter GPS’ on our iphones. This didn’t need an internet connection. We also printed out a good detailed map from www.wikirutas.es.

He also warned us not to rely on cairns and red marks painted on the rocks. “They would only lead you to the wrong place”, he said. I started to feel overwhelmed. My nervousness was raising by the minute.

However, at 15.00 in the afternoon, we still drove up to the car park, packed up all our stuff and headed off to the refuge. It was hot, sunny and clear. We were hoping that the weather would hold like this up there. Clear visibility is crucial in the mountain, not only does it give you spectacular view but, more importantly, it helps you navigate around the mountain.

The refuge was only a 40 minutes walk from the car park. The path was paved with big, flat stones, it was an easy walk. I bet lots of casual walkers would go up to the refuge in summer for a nice stroll.

Below, el “robameriendas”, (in English, “the dinner stealer”) a flower that comes up in autumn to announce that the cold weather is coming. Quite pretty and a lonely flower in the autumn landscape.

Soon after we started the walk, we spotted the refuge. It was only another twenty minutes away.

More than a refuge, it looked like a farm. There were donkeys wandering around everywhere.

And dozens of cats, which laid clustered on the floor, in front of the doorstep, in everybody’s way. The next morning, when it was still dark, I trod on them when I left the refuge. I bet one wouldn’t be able to walk very well for a couple of days. Stupid cats!

Before I entered the refuge, we carefully studied the route for the next day. It didn’t seem too difficult to spot the starting path, however, this was soon lost in a jumble of rocks.

The snow, visible from the refuge, belonged to the glacier of Maladeta, which according to the map, we would leave on the right hand site. “Good” I thought, not sure if I could cope with doing two glaciers on this walk.

The tension was building inside me. The more I read about the route the more anxious I got. I started to feel butterflies in my stomach. This is my normal feeling before I climb a challenging mountain; a combination of excitement and nervousness.

We entered the refuge and checked in. Yes, the host was as miserable as he sounded on the phone. We headed off to our room to sort out our bags for the next day. Lunch, first aid kit, rope and climbing equipment… We must not forget anything.

We were the only ones in the refuge that night, so we had plenty of beds to choose from.

We checked the state of the equipment. Crampons were now well adjusted to the boot. No risk of them slipping out on the snow.

The kitchen was big, but cold.

We would have to cook quickly and move to the lonely and dark dinning room to eat, this at least had a heater.

First things, first. We filled up our water bottles with our water filter. We don’t trust the cleanliness of the water up there in the mountains.

To keep our mind from the climb, we tried to relax with a bit of red wine.

And a nice dinner. As a starter, we opened tins of mussels in vieira (a sauce from Galicia) and octopus in olive oil.

followed by chicken stir-fried with peppers, onions and a bit of grand masala (an Indian spice). Unfortunately, my understanding of ‘a bit of grand masala’ was slightly different from Gary’s. He put a bit too much, and as I am not used to spicy food, my nose kept running well after we finished dinner.

The day of the trek. We had an early start, 6.30 am. We understood it should take us six hours to reach the summit and five hours to return, meaning we would get back to the refuge by 18.00. This would still give us half an hour as a contingency, pretty tight. We might end up returning to Dora in the dark.

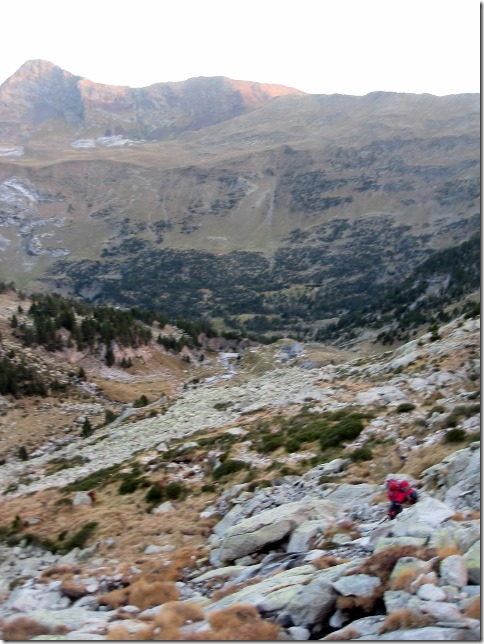

The terrain rapidly changed from steep grassy flanks to gigantic boulder fields which I had to negotiate by using knees and hands, which slowed me down. Gary continuously hurried me up. This made me feel psychologically tired.

An hour later, the sun started to rise. The landscape, bathed with a clear and bright sunlight, was spectacular. Luckily, the day promised to be hot and sunny. Stable conditions were needed to tackle Aneto.

Patches of ice covered the boulders. These are dangerous hazards that could cause fatal accidents if we were not careful. At times, you had no choice but going around them, looking for better and safer routes which made us waste time.

When we finally got to the ridge, we checked our altimeter. We disappointedly found out that after one and a half hours, we had only climbed 300 metres, we still had 500 metres to go to find Portillon Superior. We had to press on.

It was getting quite warm. I would have happily taken off two or three layers, including my wool hat, but we couldn’t waste more time with frequent stops.

The views, though, were stunning. It promised to be an spectacular summit (if we succeeded).

After walking for another hour, we checked our altimeter again, we were at 2,600. We had 200 meters more to go.

We started to see the glacier. I understood why so many people had made mistakes at this point. The route to the glacier was so clear that you could be tempted to cross to the other side and continue to find the route. However, the route down the cliff looked treacherous, we were not tempted to dismiss the advice we had been given.

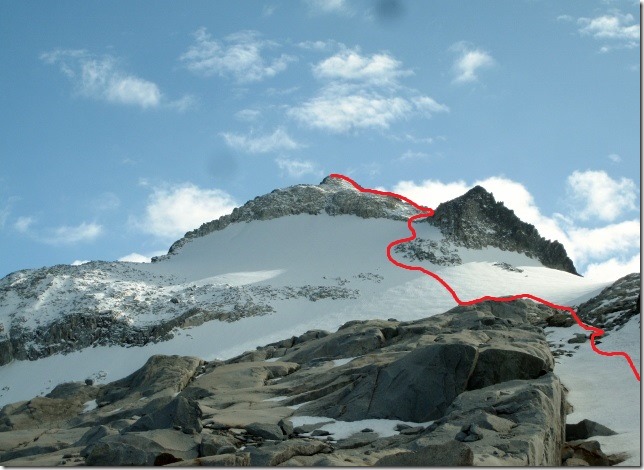

After a further forty five minutes, we checked the altimeter and it marked 2,800. We looked down, an easy path seemed to lead through the ridge to the route of the glacier beyond. The glacier that hang from Pico Aneto stood in front of us. We were at the right crossing point. We had found the Portillon Superior with not a great deal of difficulty, except that it had taken us two hours and forty five minutes, an hour more than we anticipated. We really had to walk fast from then on if we wanted to get back in daylight.

We headed off to the upper route of the glacier, which was clearly visible from the ridge. To get there, we had to climb up a series of steep snow slopes. The snow was hard and icy, slippery at times. Stepping firmly and confidently was crucial to keep your balance. A sharp kick of the boot ensured stability. We did not yet want to put on our crampons as there was a series of rocky patches to overcome. The crampons would have to wait for the glacier proper.

We finally arrived at the starting point of the glacier. We put our crampons on and replaced our poles with our ice axes. The route was well-marked with the footsteps of previous walkers. The snow was solid. It was obvious that lots of people were still climbing Aneto, making the most of the nice weather.

Although we didn’t need to, we wanted to gain experience and therefore roped up. This was also to prepare us for when we crossed the Puente de Mahoma.

The sun started to hide behind the clouds although the day continued to be clear and bright. Still the perfect conditions.

Walking with ropes reduces the risk of falls but it slows you down. However, we seemed to be moving fast. We were making up the time we had lost climbing up to the Portillon Superior.

We got to the ridge of the glacier earlier than expected. We were doing well.

It took us two hours to cross the glacier (half an hour less than anticipated). Four climbers were turning back after reaching the summit. “Venga que ya falta poco” (in English, “come on you are nearly there”) they shouted, encouraging us.

I was quite happy. We had gone through the two risky points without much difficulty: the Portillon Superior and the glacier. The one I feared most though, was still to come: the Puente de Mahoma. I got goose bumps every time I thought about it. “Maybe it is not as bad as people say” I thought. I wasn’t that lucky.

We walked up a few metres and there it was; a wall of sharp boulders. This ridge was so narrow that you couldn’t stand up on it. To cross it, you had to either walk on your bum or scramble across the rocks. There appeared to be a 1,000 metres fall on each side. I was petrified. The vertigo was extreme. I wondered how Gary felt.

You had no choice. You had to get over it. The summit was just there, only 30 metres away. You could almost touch it, you couldn’t turn back now. I went across by continuously looking ahead, repeating, “come on, you are almost there, but don’t look down, for goodness sake!”

Gary got to the top before me. According to him, I was walking up with a massive smile on my face. We did it, we had climbed Aneto.

There was no one else on the summit, so we took a photo of ourselves as best we could. We both are a bit lopsided as we couldn’t find a flat area for the camera.

The views from the summit were breath-taking.

At this point, we realised why we had put ourselves through so much stress. We really felt we were on the top of the world. The feeling of achievement was incredibly overwhelming.

This was so impressive, we felt dizzy and so small.

We had a quick lunch. It was getting quite cold. It was then when I realised we still had to go back across the bloody Puente de Mahoma.

We were still roped up. Gary wanted me to lead, the heavier person should always be up the slope, which is why he summited first. To safely cross the ridge I draped the rope around some of the more stable rocks. Should I fall, the rope would snag and prevent me from falling further, or that is a theory! We both crossed successfully. We were relieved, that bit was over.

We took a different route on the way back, one that went straight down the glacier. It was much quicker. We had left the glacier behind in one hour.

We were wondering why people don’t take this route up. It seemed to me much quicker going up the glacier this way, rather than taking the route through the Portillon Superior.

Soon after, I realised why. A huge variety of terrain ranging from sharp rocky ridges, gigantic boulder fields and glass smooth granite slabs needed to be navigated to successfully go down. Climbing up on this type of terrain would have been very dangerous. The risk of falling and killing yourself by hitting a boulder was much higher, as these rocks would have been covered by ice all the way up, early in the morning.

The trail funnelled down to eventually reach a path leading us to the refuge. There were no markers or cairns to enable us to find the route. But this was the only way to get out of the valley, so we didn’t need them.

However, going the other way, up, would have been much more difficult to navigate. The terrain was really monotonous and you could not see your destination beyond, as the glacier was not visible for another 1,000 metres. Besides, the landscape was particularly unattractive. We much preferred our route up, even though it had the difficulty of the Portillon Superior.

Two hours later we found the path to the refuge. The rocks gradually disappeared, which our knees were grateful for. At that point, they were starting to disintegrate. I was so thankful for the poles.

One hour and a half of a relatively easy path brought us to a steep climb. This lasted half an hour. Someone was testing us to see what energy we had left. Only the thought of a nice dinner in Dora with a nice glass of cold white wine kept us going.

We reached the refuge at 17.00, we were delighted, it was still day-light. We settled the bill with our miserable host and, forty minutes later, we were down in the car park.

When we got to Dora, I almost collapsed. I felt exhausted but incredibly satisfied. Gary and I hugged each other. I love this part of the day. The sense of achievement is overwhelming.

Driving back to Benasque, Gary came up with the idea of having pizza for dinner. Bizarre suggestion as we very rarely eat pizza but I liked the idea of not cooking that night, we were so exhausted. So I agreed. It just so happened that we were in the only town in the world that didn’t have an open take away pizza shop. The locals told us that all the shops had shut down for the season. We couldn’t believe our luck.

We found a Spanish bar which did tapas to take away. A much better option than the pizza, anyway. We had a cold glass of white wine to celebrate our accomplishment. All the stress had already gone. We were almost ready for our next climb.

SM

![2014-10-30 Pico Aneto (31) (640x439)[1] 2014-10-30 Pico Aneto (31) (640x439)[1]](https://www.2wanderers.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/2014-10-30-Pico-Aneto-31-640x4391_thumb.jpg)

Very well written and detailed article!! Its just like as though I had been trekking with you there…´

One more summit is on your pocket!! Congratulations cuople of wanderes.

Thanks Brother. It was Once of our best summits

Enhorabuena por el objetivo conseguido, no quiero opinar de la subida, me dan escalofríos .

muchas gracias!

Guau, that was amazing, the story is incredibly exciting, it makes you want to get the hiking boots on and get out. Incredibly exciting and energising, thank you for sharing with us!

Thanks! it was incredibly rewarding. Next time you come with us

Your next climb? I am exhausted just by reading!!

Why don’t you take a couple of days just to relax??!!

I

We tried that, got bored and started to look for the next mountain

GDR